Decolonising Collections

ETH Library’s Current Initiatives

1. Decolonising collections at ETH Zurich

Despite Switzerland’s lack of involvement in colonialism as a traditional imperial power, it nevertheless played a significant role in the military, economic, and scientific dimensions of colonialism, both directly and indirectly.1 Switzerland’s involvement left its mark on its museums, archives and collections.2

The history of ETH Zurich and its historical collections also reflect Switzerland’s colonial entanglements.3 Scientists from Switzerland, many of whom were affiliated with ETH Zurich, used the infrastructures and asymmetrical power relations of neighbouring colonial powers to advance their research careers and collect comparative material from around the world. This has left numerous traces, including in the monuments on display at ETH Zurich and in its collections and archives. The written and photographic legacies of individual so called explorers, as well as botanical, geological or entomological specimens from colonial contexts, bear witness to Swiss connections between science and colonialism.

Against this background and inspired by the current international debate on decolonisation, the ETH Library plays an important and active role in the critical examination, reappraisal and mediation of this challenging legacy. In collaboration with the natural history collections and specialised archives of the departments of ETH Zurich, and with internal and external experts and committees, its collections and archives are currently active in three areas:

- The internal decolonisation working group focuses on the specific issues that arise in the cataloguing, digitisation and online presentation of colonial holdings, and how these should be dealt with in day-to-day practice.

- The temporary exhibition “Colonial Traces – Collections in Context” examines the traces of colonialism in the collections and archives of ETH Zurich, focusing on a selection of objects.

- The project “Monuments in Context” critically analyses the physical culture of remembrance at ETH Zurich and contextualises monuments to researchers and personalities who, from today’s perspective, represent problematic ideas and ideologies.

These initiatives, which are embedded in an academic and socio-political discussion, are presented in more detail below.

2. Working Group “Decolonisation”

ETH Zurich houses over twenty specialised collections and archives within its departments and the ETH Library.4 These units are responsible for enabling research, ensuring the preservation of their holdings and disseminating information about them. Many of their holdings reflect Switzerland’s diverse colonial ties.

2.1 Members, goals and result of the working group

The Decolonisation Working Group, established in August 2023, focuses on examining the practices of cataloguing, documenting, and presenting colonial collections at ETH Zurich. It comprises staff from various collections and archives – including the Archives of Contemporary History, the Image Archive, the Earth Science Collections, the Collection of Prints and Drawings (Graphische Sammlung ETH Zürich), the gta Archives (Architecture), the Literary Archives (Max Frisch Archive and Thomas Mann Archive), the unit Rare Books, Maps and Geoinformation, the ETH Zurich University Archives and the Collection of Scientific Instruments and Teaching Aids.

The collections and archives of ETH Zurich are very heterogenous, covering a wide range of materials such as art, objects, and documents from natural sciences, technology, and culture. These collections, rooted in distinct research and teaching contexts, reflect ETH Zurich’s colonial entanglements in several ways. While e.g. the Earth Science Collections contain objects directly from colonies, many other holdings are indirectly linked to colonial or imperial ideologies and practices, including racist notions of Western superiority used to justify exploitation and oppression. It is therefore crucial to rigorously scrutinise the colonial legacies embedded in the holdings of the collections and archives, acknowledging the colonial thought patterns and histories they reflect.5

The task of the working group is to analyse these holdings, identify problematic areas, and develop strategies for the future that ensure the authenticity of the holdings and access for researchers. The first initiative was an internal anti-racism workshop led by the social and cultural anthropologist, actress and consultant Danielle Isler6, aimed at addressing unconscious bias. The group’s efforts culminated in the “Decolonising the Collections and Archives of ETH Zurich”7 guideline, which was published in August 2024 on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition “Colonial Traces – Collections in Context.” The guideline primarily provides practical examples of colonial documents and objects, as well as strategies and recommendations for dealing with them.

Key questions guiding this process include: (1) What do we mean by colonialism? (2) How and why is a collection/ an archive colonially influenced? (3) How can staff be empowered and educated? Further questions cover acquisition, cataloguing and presentation, such as how to handle discriminatory terminology or present sensitive content online or in exhibitions.

Based on these questions, on comparable guidelines from other institutions8 and on the exchange with other working groups in the field,9 the group developed measures and recommendations regarding – among other issues – terminology (e.g., explicit and transparent separation between original titles and new descriptions), image use (e.g., restricting access to discriminatory images to scientific use on demand), presentation (e.g., publishing ethical guidelines on platforms), and collection development (e.g., closing existing gender gaps in the collections where possible). Though the guideline is not exhaustive, it provides a framework for identifying decolonisation needs. Regular updates will ensure its relevance as the field evolves.

2.2 Example: The holdings of Arnold Heim

The personal collection of the petroleum expert (petrogeologist) Arnold Heim is an illustrative example included in the guideline. Heim was born into a bourgeois family in Zurich on 20 March 1882. His mother, Marie Heim-Vögtlin (1845–1916), was the first female practising Swiss medical doctor and his father, Albert Heim (1849–1937), was a renowned professor of geology at ETH Zurich. Arnold Heim received his doctorate in geology from the University of Zurich in 1905. He then worked as a private lecturer at ETH Zurich and at the University of Zurich. From 1929 to 1931, he was a professor at the University of Canton in China. He also participated in numerous scientific expeditions around the world. These were often commissioned by private or state companies. In 1909, for instance, he undertook a search for coal and mineral deposits in Greenland on behalf of the Danish Grønlandsk Minedrifts Aktieselskab. In 1926, he accompanied the aviation entrepreneur Walter Mittelholzer, the writer René Gouzy, and the mechanic Hans Hartmann on their so-called “Africa Flight”, which was the first flight in a seaplane from Switzerland to South Africa. In 1936, he undertook an expedition to the Himalayas with the Swiss geologist Augusto Gansser. The eight-month expedition served as a precursor to the subsequent colonial race between the British and the Swiss for the first ascent of Mount Everest.10

But his expeditions were not all scientific. From 1910 until the 1950s, he worked as a petrogeologist for a number of companies, including Shell and the Iran Oil Company. His work took him to places as diverse as Sumatra, Java, California, Mexico and to the former territories of present-day Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Bahrain. Heim was considered one of the most internationally renowned mineral oil experts of his time. He also achieved considerable fame beyond academic and professional circles through his numerous travel books, such as the highly popular “Weltbild eines Naturforschers”, published in 1942.11

On behalf of an oil company, Arnold Heim made several trips to the Indonesian archipelago under Dutch colonial rule in the early 20th century. During his travels, he kept a diary and corresponded extensively by letter. These texts include a number of passages containing stereotypical, racist descriptions and drawings.12 He also documented his observations in field books and collected stone and oil samples during his expeditions. As a result, he brought samples back to Switzerland that were collected during formal colonial rule. Some of the stone samples Heim collected can still be found in the Earth Science Collections.13

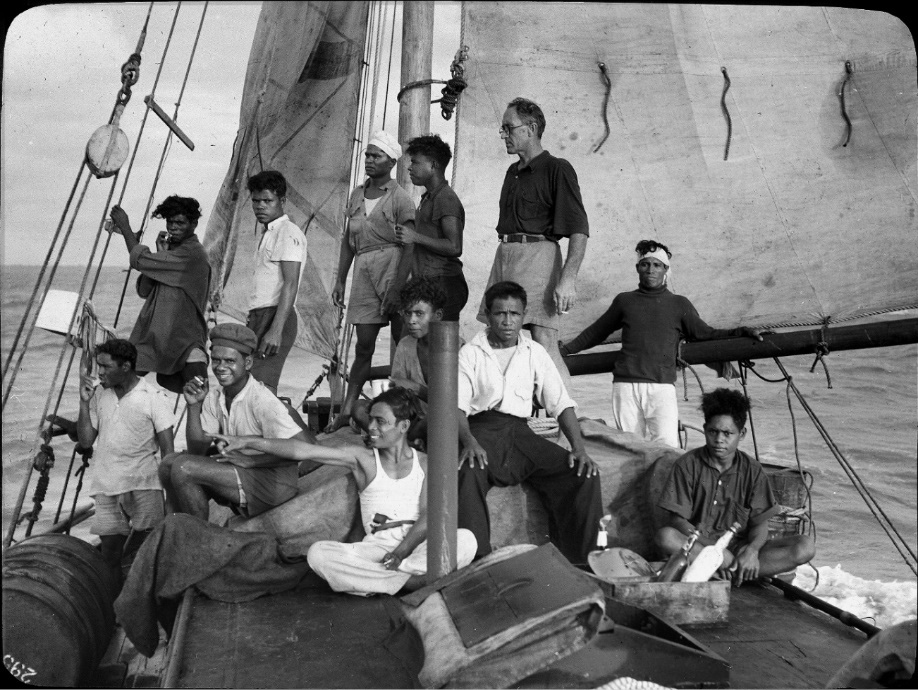

The Image Archive also houses Heim’s photographic archive. It contains a substantial number of photographs taken during his expeditions (see fig. 1). Some of these images and their original metadata contain discriminatory, racist, and/or sexualising content. They reflect the exploration of peoples and cultures using scientific methods and concepts that were prevalent during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Based on the views and his ‘colonial gaze’ detailed in his “Weltbild”, Heim also deliberately used the medium of photography to stage and to other colonised people as ‘natural people’, a state he believed to be lost in Western civilisation.14

Arnold Heim’s entire image collection has been catalogued and digitised by the Image Archive. However, not all digitised images are freely accessible via the online platform E-Pics Image Archive.15 To ensure transparency, the collection description makes explicit reference to sensitive content and the restriction on online access: ‘[The collection] contains discriminatory and sexualising depictions of people. These images are therefore not accessible online. However, they are available for research purposes on request.’ 16

In the guidelines, the Image Archive’s practice in dealing with images from colonial contexts is further detailed.17 However, the question of which digitised images are not made directly accessible online (e.g., clearly pornographic images or depictions of extreme violence) is only one aspect. The handling of metadata is equally important. To enable historical research, original metadata remains searchable in the database even if it contains terms that are sensitive from today’s perspective. They are made accessible via appropriately labelled elements such as ‘original title:’. In the future, however, more emphasis will be placed on additional context information for certain types of images. This applies to anthropometric images, for example, but also to photographs that show cases of blackfacing. The established crowdsourcing of the Image Archive can also be used to identify relevant images and to include specific information from users worldwide.18

The holdings of Arnold Heim represent only one of numerous sources of Swiss entanglement in the colonial exploration, control and exploitation during the era of imperialism. Other valuable sources include the private collections of Walter Mittelholzer, Alfred de Quervain and Augusto Gansser, among others, which are available for further research from the ETH University Archives and from the Image Archive.

3. Exhibition “Colonial Traces – Collections in Context”

While the activities of the working group focus on all the key functions of collections and archives, the exhibition “Colonial Traces – Collections in Context” specifically focuses on mediation and presentation. This temporary exhibition runs from 30 August 2024 to 13 July 2025 in the exhibition space “extract” on the ground floor of ETH Zurich’s main building (see fig. 2).19 Opened in 2023 by the ETH Library, extract aims to bring together the heterogenous collections and archives of ETH Zurich to illuminate important contemporary topics. The focus is on cross-disciplinary issues of social relevance, rather than on a single collection or archive. The advisory board of the exhibition space, including representatives from the Swiss National Museum, the University of Zurich, and the Zürcher Museumsverein, strongly supported the proposal to focus on the topic of colonialism in the collections, which aligns with other concurrent Zurich exhibitions.20

The exhibition team, coordinated by ETH Library’s Agnese Quadri (Collections and Archives), includes external experts: Monique Ligtenberg as curator, Charles Job and Maude von Giese for scenography, and Devika Salomon for graphic design.

Developed and approved in spring 2024, the exhibition’s concept outlines three goals:

- Informing about ETH Zurich’s colonial past and its collections,

- Raising awareness of the link between scientific knowledge production and colonial violence,

- Contributing to discussions on addressing the lasting legacies of colonial entanglements in the natural sciences.

The exhibition’s narrative starts with the colonial past and moves to the post-colonial present. At the core of the historical section are three modules, each exploring a specific aspect of why ETH Zurich houses so many objects and archival materials from colonial contexts. The first module, “Colonial Provenances – Journeys of Objects”, reexamines the objects themselves and the circumstances of their (potentially violent) acquisition, transport, and arrival at ETH Zurich. The second module, “Researching in Colonial Contexts”, examines the role of colonial collecting and research in the careers of individual scientists affiliated with ETH Zurich. Particular attention is paid to the knowledge and labour of indigenous experts in the expeditions of ETH researchers. The third module, “Science and Colonialism”, investigates how the knowledge produced by Swiss researchers was used for the ecological, economic, and military exploitation of the colonies, e.g. in the plantation economy and in the planning and implementation of settlement projects.

The fourth module, “Postcolonial Continuities”, is spatially distinct and focuses on the long-term ecological, social and political consequences of ETH’s colonial past and global scientific collaborations in the present. It highlights both the scientific efforts to address global inequalities and the unresolved challenges. The exhibition aims to engage visitors in reflecting on how to confront and overcome colonial legacies.

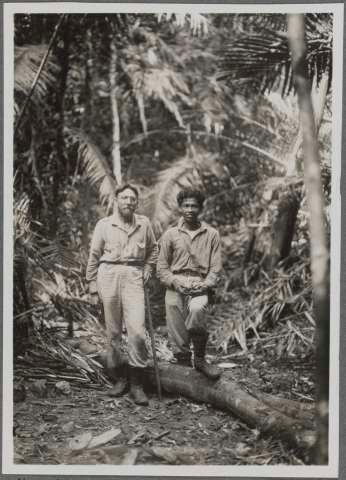

One of the challenges facing the exhibition team was how to exhibit gaps in the archives. For instance, the role of indigenous experts in knowledge production was often minimised or erased by European researchers during the colonial era. Photographs like the one from Sumatra in 1928, showing Arnold Heim and the surveyor Suriadi side by side (see fig. 3), are rare exceptions.

The exhibition also highlights the contributions of women scientists in the colonies, though they were few in number. Baroness Margarete von Uexküll (1873–1970) exemplifies the ambivalence common to many European women in the colonies. Born in Russia, she studied natural sciences in Zurich and Geneva before conducting research in the Dutch East Indies. While she challenged bourgeois, patriarchal gender roles, von Uexküll did not align with the colonised population, unlike Swiss feminist Frieda Hauswirth, who linked feminist concerns with anti-colonial struggles.21

4. Monuments in Context

Another key aspect of examining ETH Zurich’s colonial heritage is addressing elements that aren’t immediately apparent, such as the university’s monuments. Over 100 monuments, commemorating individuals from Switzerland and abroad since ETH’s founding in 1855, are part of this physical culture of remembrance.

The ETH Library is connected to this culture in two ways. First, its representatives – the Heads of the Collection of Prints and Drawings ETH Zurich and the Collections and Archives – sit on the Art in Architecture Commission, chaired by the Vice President for Infrastructure. This commission oversees new art projects and the preservation of existing monuments. Second, the Library manages the ETH Zurich Art Inventory, cataloging these monuments and ensuring their restoration.22

In response to recent international re-evaluation of monuments in public space, which also led to controversial debates in Zurich,23 the Commission for Art in Architecture commissioned historian Monika Gisler in 2022 to assess whether individuals commemorated by ETH monuments were involved in colonialism or expressed racist, anti-Semitic, or sexist views.

The study’s findings were clear: “Around two thirds of the people examined expressed racist, sexist or anti-Semitic views in one form or another, profited from colonialism or contributed to its legitimisation through their writings.”24 A prominent example is geologist Charles Lyell (1797–1875), whose scientific racism helped justify the colonisation of non-European regions despite his fundamental contributions to the understanding of Earth’s geological development.25

The results of the preliminary study prompted the Art in Architecture Committee to take action. In April 2024, ETH Zurich’s Executive Board approved the Commission’s proposal for the multi-year “ETH Decol Initiative” (2024–2029). Developed in collaboration with Harald Fischer-Tiné, Chair of the History of the Modern World at ETH Zurich, the initiative has two main goals. First, it will launch research projects on ETH Zurich’s institutional history, led by the chair. A key project, “Swiss Science in the Service of European Expansion: ETH Zurich and its Colonial Entanglements (1880–1960)”, focuses on ETH’s involvement in colonialism, including how colonial infrastructures supported research and careers, expanding on insights from the exhibition.

The second aim is to update ETH Zurich’s culture of remembrance. As a first step, the study’s recommendation to contextualise selected monuments will be implemented in two phases. First, on-site signage will provide brief background information; then, an online virtual tour will offer deeper insights into the monuments and the individuals commemorated. In the coming years, international artistic interventions will further engage with these monuments.

5. Conclusion

Switzerland has recently begun to critically examine its colonial entanglements, initially focusing on ethnographic museums but now expanding to other sectors. The ETH Library exemplifies how academic memory institutions can play a proactive role in globally connected universities. This includes reflecting on internal practices such as cataloguing and digitisation, promoting research, participating in discussions at various levels, and implementing both analogue and digital mediation.

The challenges are considerable. The diversity of collections and the lack of uniform practices require the balancing of multiple perspectives, leading to constant revision and adaptation. The decolonisation of archives and collections is a vital but complex task.

However, decolonisation efforts cannot rely solely on collections and archives. It is the collective responsibility of all GLAM institutions and society to work together to drive this change. Decolonisation is a shared concern, linked to the broader question of the kind of world we want to live in.

Citable Link (DOI): https://doi.org/10.5282/o-bib/6066

This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

1 See e.g.: Fischer-Tiné, Harald; Purtschert, Patricia (ed.): Colonial Switzerland. Rethinking Colonialism from the Margins, London 2015, and Swiss National Museum (ed.): colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entaglements, Zurich 2024.

2 See e.g.: Tisa Francini, Esther; Hertzog, Alice et al. (ed.): Mobilizing. Benin Heritage in Swiss Museums, Zurich 2024.

3 This paper refers to the presentation “Decolonising Collections. ETH Library’s Current Initiatives” by the authors on 6 June 2024 at BiblioCon 2024 in Hamburg, Germany.

4 ETH Zurich: Collections and Archives, https://ethz.ch/en/campus/getting-to-know/learning-and-working/collections-and-archives.html, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

5 See Willi, Stephanie: Weisses Papier, weisse Archive. Über die Notwendigkeit der Dekolonisierung von Schweizer Archiven, in: Informationswissenschaft. Theorie, Methode und Praxis 8 (1), 2024, p. 449-484. https://doi.org/10.18755/iw.2024.22.

6 Danielle Isler, https://www.danielle-isler.com/about, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

7 Arbeitsgruppe Dekolonialisierung, Sammlungen und Archive der ETH Zürich (ed.): Dekolonialisierung der Sammlungen und Archive der ETH Zürich. Ein Leitfaden aus der Praxis, Zürich 2024. https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000691291.

8 E.g. German Museums Association (ed.): E-reader Care of Collections from Colonial Contexts, Berlin 2021. Online: https://www.museumsbund.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/e-reader-care-of-collections-from-colonial-contexts.pdf, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

9 E.g. Netzwerk Dekolonialisierung von Bibliotheken im DACH-Raum, https://hcommons.org/groups/netzwerk-dekolonialisierung-von-bibliotheken-im-dach-raum/ or Netzwerk koloniale Kontexte, https://www.evifa.de/de/netzwerk-koloniale-kontexte, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

10 See Gisler, Monika: ”Swiss Gang” – Pioniere der Erdölexploration, Zürich 2014.

11 See Heim, Arnold: Weltbild eines Naturforschers. Mein Bekenntnis, Bern 1942.

12 See ETH Library, ETH Zurich University Archives, Hs 494:244 until Hs 494:247.

13 See Arbeitsgruppe Dekolonialisierung, Sammlungen und Archive der ETH Zürich (ed.): Dekolonialisierung der Sammlungen und Archive der ETH Zürich, 2014, pp. 26–29.

14 Gasser, Michael: Naturmenschen statt Wilde. Arnold Heims Blick auf Schwarzafrika als Teilnehmer an Mittelholzers Afrikaflug von 1926/27, in: ETH-Bibliothek (Ed.): Forscher auf Reisen. Fotografien als wissenschaftliches Souvenir, Zürich 2008, pp. 99–114.

15 ETH Zürich Image Archive: Arnold Heim (1882-1965, geologist): https://ba.e-pics.ethz.ch/catalog/ETHBIB.Bildarchiv/c/6646, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

16 Ibid.

17 See Arbeitsgruppe Dekolonialisierung, Sammlungen und Archive der ETH Zürich (Ed.): Dekolonialisierung der Sammlungen und Archive der ETH Zürich, 2024, pp. 18–22.

18 See ETH-Bibliothek Crowdsourcing. News and experiences from the community, https://crowdsourcing.ethz.ch/en/, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

19 https://extract.ethz.ch/en/exhibition.html#extract2024, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

20 Swiss National Museum: colonial. Switzerland’s Global Entanglements (13.09.24 to 19.01./25); Ethnographic Museum Zurich: Benin Dues. Dealing with Looted Royal Treasures (24.08.24 to 14.09.25); museum rietberg: In Dialogue with Benin Art, Colonialism and Restitution (23.08.24 to 16.02.25).

21 Blaser, Claire Louise: „Hauswirth, Frieda“, in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version of 18 October 2021. https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/059668/2021-10-18/, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

22 Art Inventory of ETH Zurich. https://ki.e-pics.ethz.ch/, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

23 See Kreis, Georg: Die öffentlichen Denkmäler der Stadt Zürich. Ein Bericht im Auftrag der Arbeitsgruppe KiöR, 30. Juni 2021. Gesamtbetrachtung zu 38 in separaten Texten dokumentierten Denkmälern, Zürich 2022. Online: https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/ted/de/index/departement/medien/medienmitteilungen/2022/april/220413d.html, last accessed 17.09.2024.

24 Gisler, Monika; Gisler, Lina: Denkmäler der ETH Zürich. Bericht zu Händen der Kommission für Kunst am Bau der ETH Zürich, 30.11.2022, p. 18. Online: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000644208, last accessed: 17.09.2024.

25 Cf. ibid., p. 21, 117f.